Why does running have to hurt?

Posted by Adam Stuhlfaut, Director of Running on

When I think of the pain associated with running I think in two categories. First there is the general, “It hurts to get out and start running.” This hurt is part physical as your sedentary body makes the necessary adjustments to running. The lungs need to wake up to the increase breathing. Muscles that are tight from a long night sleep or a long day in the office ache and creek as they slide into gear. The second category of pain is associated with specific body parts and always leads to the age-old question: “Am I sore or am I injured.” All runners get some common aches and pains that can be “run-though” while other pains are a warning sign to stop.

Take-offs can be a bumpy ride

I’ve been a runner for thirty-years and one thing I can tell you is that the first steps are always hard. As I get older, the time it takes for my body to warm-up only increases. The first mile or two is a challenge both physically and psychologically. Just like the body needs to warm-up, it can take time to get over the psychological hurt of being comfortable and sedentary. For thirty years I’ve often asked myself “why”. “Why am I out here? What am I doing? Why do I put myself through this?” More than psychological, this questioning is part of the spiritual quest of being a runner. For me the answer is found much later after I’m warmed up or even after the run. In those times, we bask in the glow of the effort and take pride in our resilience.

“Am I sore or am I injured.”

Even with experience it can be difficult to tell the difference between being sore and being injured enough to stop. The challenge is deciding, when a particular body part hurts, whether it’s a good idea to keep running or it’s better to take time off. The result of the wrong choice is the same. The peril of running when you are truly injured is a potentially long layoff, while the peril of not running when just sore is also taking unnecessary time off.

One good example of a running soreness is pain in the shin area often known as shin splints. The shin areas take a beating for several reasons. The bones, tendons and muscles can have trouble adjusting to impact loading as you ramp up the miles. Also, you can have irritations of long tendons that originate in the shin area and attach in your feet. One such common ailment is called Posterior Tibial Tendonitis. This Posterior Tibial Tendon can be sore anywhere from its attachment in the feet, to the inside of your ankles to high upper in the shin bone. It gets aggravated for lots of reasons. For example, increased impact loading on your arch yanks and pulls at the tendon and irritates it. It gets irritated often for many runners, but many runners also find that they can run though this pain by using proper warm-ups, stretching and icing as aides.

How do I know the difference?

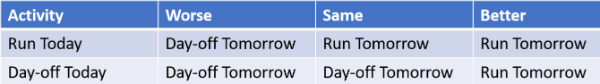

Okay, so how do know the difference (besides going to the doctor)? My rule of thumb on injuries is if each day the affected area is the at least the same or slightly better, I continue to run. If worse I start taking days off. If on the day off it starts feeling better, I run the next day. If it’s the same or worse, I take another day off. The below table gives a simplified summary of thought.

Here’s where I always give the disclaimer to check with your trusted medical professional.

As always, please verify this and any information that relates to potential injuries with a trained and educated medical professional. My advice on top of that disclaimer is to make sure your medical professional has a good history in dealing with running injuries because many runners often stop running on the advice of a medical professional, when those of us with lots more practical experience know it’s probably okay to run through. So, listen to your doctor or physical therapist, just take the time to understand their qualifications.

Also, don’t just talk to your “neighbor the runner” or your “cousin the runner” who might be helpful with relaying information about their personal situations, but don’t understand that one data point (also known as anecdotal data) is not enough data to prove any theory.